Python String Templates

Categories:

Mastering Python String Templates for Flexible Text Formatting

Explore Python's string.Template module for secure and flexible string substitutions, ideal for user-provided values and internationalization.

Python offers several ways to format strings, from f-strings and the str.format() method to the older % operator. However, for scenarios requiring greater security, flexibility, or when dealing with user-provided substitution values, the string.Template module provides a robust and often overlooked solution. This article delves into the string.Template class, explaining its benefits, usage, and when to choose it over other string formatting techniques.

Why Use string.Template?

The primary advantage of string.Template lies in its safety when handling untrusted input. Unlike str.format() or f-strings, string.Template does not allow arbitrary Python expressions within the template placeholders. This prevents potential code injection vulnerabilities if a malicious user were to provide a substitution value that attempts to execute code. Additionally, string.Template uses a simpler, more explicit syntax for placeholders, typically $variable or ${variable}, which can be easier to read and manage in certain contexts, especially for internationalization or when non-technical users might be editing templates.

string.Template when your template strings might be exposed to user input or when you need a simpler, more explicit substitution syntax than f-strings or str.format().Basic Usage of string.Template

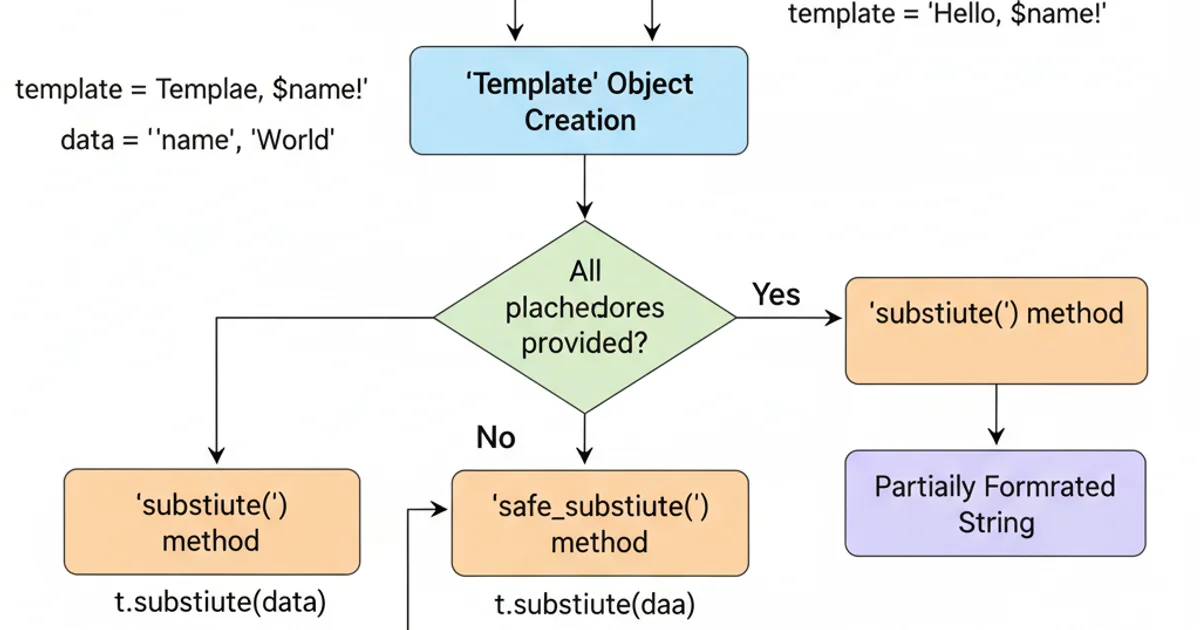

Using string.Template is straightforward. You instantiate a Template object with your template string, and then use its substitute() or safe_substitute() methods to perform the replacements. The substitute() method raises a KeyError if a placeholder is not provided in the substitution dictionary, while safe_substitute() leaves unprovided placeholders unchanged, making it more forgiving for optional values.

from string import Template

# Basic substitution

t = Template('Hello, $name! Welcome to $product.')

print(t.substitute(name='Alice', product='Our Service'))

# Handling placeholders with special characters or immediately followed by text

t2 = Template('The price is $${amount} and the item is ${item}s.')

print(t2.substitute(amount='10.99', item='apple'))

# Using safe_substitute

t3 = Template('Optional value: $optional_key. Required value: $required_key.')

print(t3.safe_substitute(required_key='present'))

# print(t3.substitute(required_key='present')) # This would raise a KeyError

Demonstrates basic string.Template usage, including substitute() and safe_substitute().

Workflow of string.Template substitution methods.

Customizing Delimiters and Patterns

By default, string.Template uses $ as the delimiter for placeholders. However, you can customize this behavior by subclassing Template and overriding the delimiter and pattern attributes. This is particularly useful if your template strings might contain $ characters that are not intended as placeholders, or if you prefer a different syntax for your variables.

from string import Template

import re

class CustomTemplate(Template):

delimiter = '%'

# Custom pattern to match %variable or %{variable}

# The default pattern is: r'\$(?:(?P<escaped>\$)|(?P<named>[_a-z][_a-z0-9]*)|(?P<braced>[_a-z][_a-z0-9]*)|(?P<invalid>))'

# We'll adapt it for '%' delimiter

pattern = r'''

%(?: # Match '%' followed by one of the following:

(?P<escaped>%) | # Match '%%', rendering as a single '%'

(?P<named>[_a-z][_a-z0-9]*) | # Match '%variable' (identifier)

(?P<braced>{[_a-z][_a-z0-9]*}) | # Match '%{variable}' (braced identifier)

(?P<invalid>) # Match '%' not followed by anything else

)'''

t = CustomTemplate('Hello, %name! Your ID is %{user_id}. The discount is %%10.')

print(t.substitute(name='Bob', user_id='12345'))

# Example with a different delimiter and simpler pattern

class BracketTemplate(Template):

delimiter = '@'

# This pattern is simpler, only matching @variable

pattern = r'@(?P<named>[_a-z][_a-z0-9]*)'

t2 = BracketTemplate('Welcome, @username! Your order number is @order_id.')

print(t2.substitute(username='Charlie', order_id='XYZ789'))

Customizing string.Template delimiters and patterns for advanced use cases.

pattern attribute, ensure your regular expression correctly captures named placeholders, braced placeholders, and escaped delimiters to avoid unexpected behavior or security vulnerabilities.Comparison with Other Formatting Methods

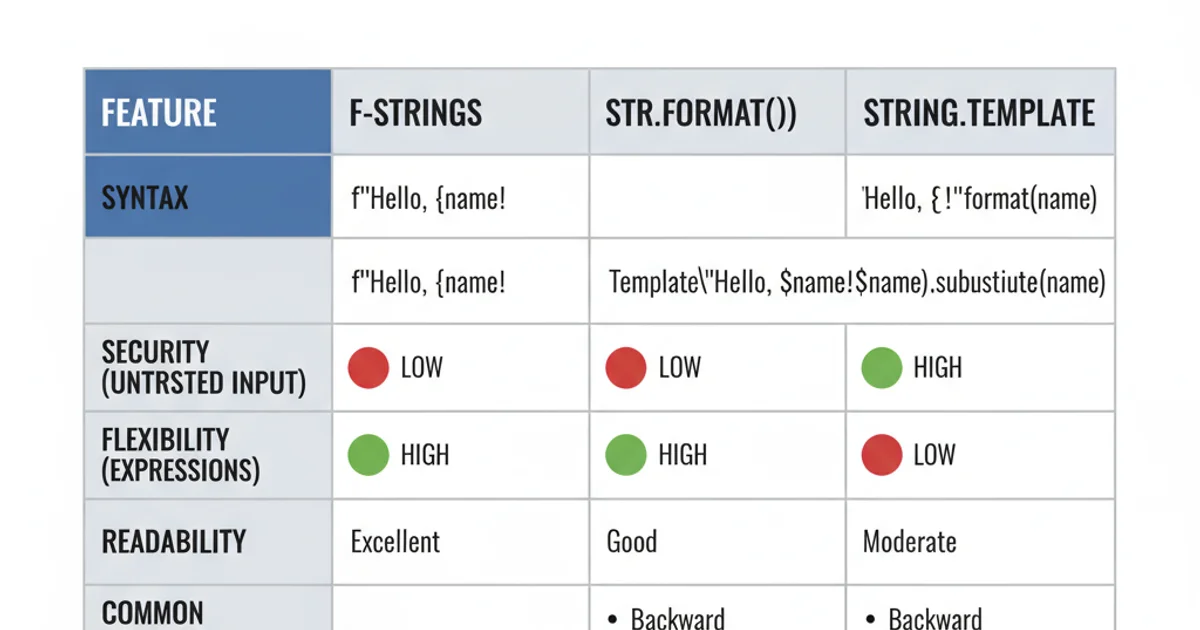

While string.Template excels in security and simplicity for specific use cases, it's important to understand its position relative to other Python string formatting methods. F-strings (formatted string literals) and str.format() are generally more powerful and concise for complex formatting, type conversions, and embedding arbitrary expressions. However, this power comes with the risk of code injection if templates or substitution values are sourced from untrusted input. The % operator is largely deprecated for new code due to its less readable syntax and fewer features compared to str.format() and f-strings.

Comparison of Python string formatting methods.

1. Import Template

Start by importing the Template class from the string module: from string import Template.

2. Create Template Object

Instantiate a Template object with your template string, using $variable or ${variable} for placeholders.

3. Substitute Values

Call template_object.substitute(mapping) for strict substitution (raises KeyError if a key is missing) or template_object.safe_substitute(mapping) for lenient substitution (leaves missing placeholders unchanged).

4. Customize (Optional)

For advanced scenarios, subclass Template to override delimiter and pattern for custom placeholder syntax.