What does "1e" mean?

Categories:

Understanding '1e' in C and Scientific Notation

Explore the meaning and usage of '1e' in C programming, its connection to scientific notation, and how it represents floating-point numbers.

In C programming, you might occasionally encounter numerical literals like 1e or 1e5. This notation is a standard way to represent floating-point numbers, particularly very large or very small ones, using scientific notation. Understanding its structure and implications is crucial for accurate numerical computations and data representation in your C applications.

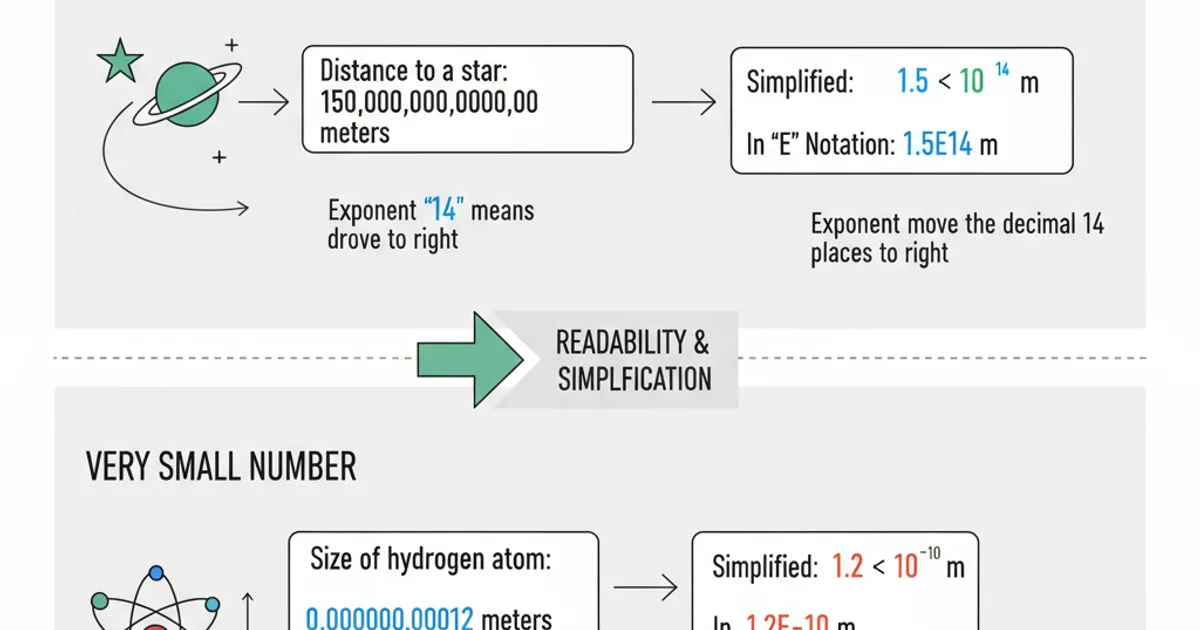

The Basics of Scientific Notation

Scientific notation is a mathematical shorthand used to express numbers that are too large or too small to be conveniently written in decimal form. It consists of a base number (mantissa) multiplied by a power of 10. For example, the number 100,000 can be written as 1 x 10^5. In programming languages like C, this is often represented using the letter 'e' (or 'E') to denote 'times 10 to the power of'.

flowchart TD

A[Number] --> B{Is it very large or very small?}

B -->|Yes| C[Use Scientific Notation]

C --> D["Mantissa 'e' Exponent"]

D --> E["Example: 1.23e-4 (1.23 * 10^-4)"]

B -->|No| F[Use Standard Decimal Notation]

F --> G["Example: 123.45"]Decision flow for using scientific notation

How '1e' Works in C

In C, 1e is not a complete number on its own. It must be followed by an exponent. The 'e' (or 'E') signifies that the number preceding it is multiplied by 10 raised to the power of the number following it. For instance:

1e5means 1 * 10^5, which evaluates to 100,000.1e-3means 1 * 10^-3, which evaluates to 0.001.1.23e+2means 1.23 * 10^2, which evaluates to 123.0.

It's important to note that the number before 'e' is treated as a double by default in C, unless explicitly cast or suffixed (e.g., 1.0f for float). If you write just 1e without an exponent, it will result in a compilation error because it's an incomplete floating-point literal.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

double num1 = 1e5; // Equivalent to 1 * 10^5 = 100000.0

double num2 = 1e-3; // Equivalent to 1 * 10^-3 = 0.001

double num3 = 1.23e+2; // Equivalent to 1.23 * 10^2 = 123.0

float num4 = 1.0e1f; // Explicitly a float: 1.0 * 10^1 = 10.0f

printf("num1: %f\n", num1);

printf("num2: %f\n", num2);

printf("num3: %f\n", num3);

printf("num4: %f\n", num4);

// This would cause a compile-time error: "exponent has no digits"

// double invalid_num = 1e;

return 0;

}

Examples of scientific notation in C

1e, will lead to a compilation error, typically 'exponent has no digits'.Why Use Scientific Notation?

Scientific notation offers several advantages in programming:

- Readability: For extremely large or small numbers,

1.23e-10is much easier to read and understand than0.000000000123. - Precision: It helps maintain precision by clearly separating the significant digits from the magnitude.

- Consistency: It provides a consistent way to represent floating-point values across different contexts and systems.

- Avoiding Errors: It reduces the chance of miscounting zeros, which is common with very long decimal representations.

Scientific notation simplifies the representation of extreme values.

Floating-Point Types and 'e' Notation

When you use scientific notation in C, the literal is typically interpreted as a double. If you need a float or long double, you must use appropriate suffixes:

1.23e5for1.23E5Fforfloat.1.23e5Lor1.23E5Lforlong double.

Without these suffixes, 1.23e5 will be a double, and assigning it to a float variable might involve an implicit conversion, potentially leading to a loss of precision if the double value exceeds the float's range or precision.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

float f_val = 1.23456789e-5f; // Explicitly float

double d_val = 1.23456789e-5; // Default double

long double ld_val = 1.23456789e-5L; // Explicitly long double

printf("Float value: %.10f (size: %zu bytes)\n", f_val, sizeof(f_val));

printf("Double value: %.10f (size: %zu bytes)\n", d_val, sizeof(d_val));

printf("Long Double value: %.10Lf (size: %zu bytes)\n", ld_val, sizeof(ld_val));

return 0;

}

Using suffixes for different floating-point types with scientific notation

double by default is often a good practice unless memory or specific performance constraints dictate the use of float.