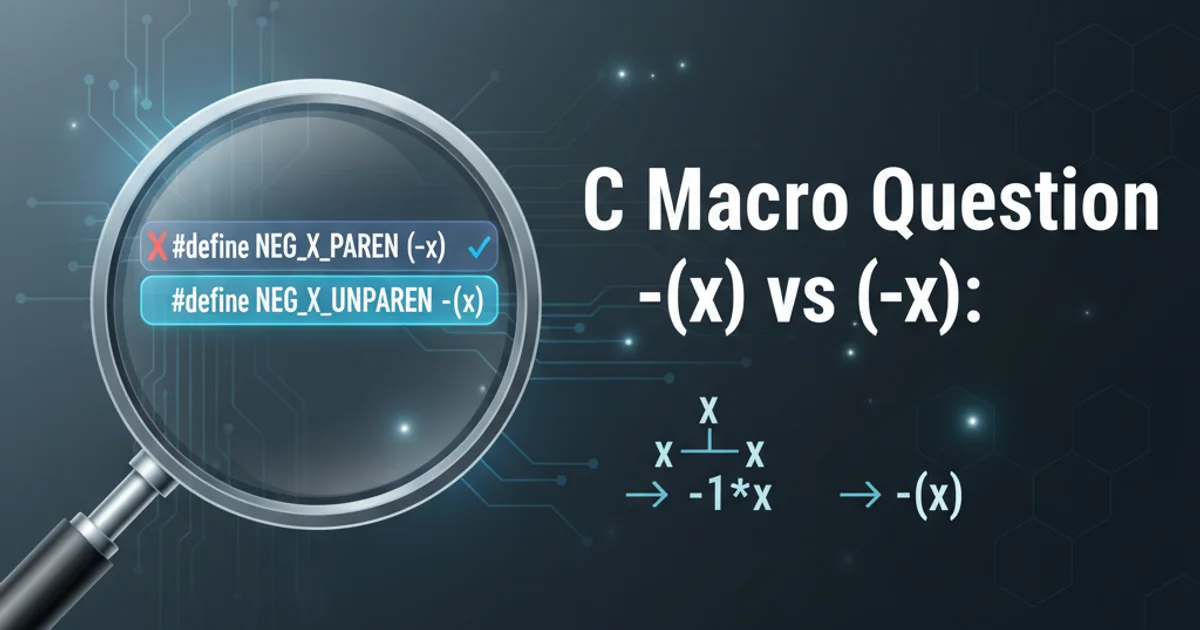

C Macro Question -(x) vs (-x)

Categories:

C Macro Nuances: Understanding -(x) vs (-x)

Explore the subtle yet critical differences between -(x) and (-x) in C macros, and learn how to avoid common pitfalls with operator precedence and side effects.

C macros are powerful tools for code generation and abstraction, but they come with their own set of challenges, particularly concerning operator precedence and side effects. A common point of confusion arises when dealing with unary minus operations within macros, specifically the distinction between -(x) and (-x). While they might appear similar, their behavior can diverge significantly when x is an expression rather than a simple variable. This article delves into these differences, illustrating why (-x) is generally the safer and more predictable choice for macro arguments.

The Problem of Operator Precedence in Macros

Macros perform simple text substitution before compilation. This means that when an argument to a macro is an expression, it's substituted directly into the macro's body. If the macro body doesn't properly parenthesize its arguments, the substituted expression can interact unexpectedly with operators already present in the macro, leading to incorrect results due to operator precedence rules.

Consider a macro designed to negate its input. If we define it as #define NEGATE(x) -x, and then call NEGATE(a + b), the preprocessor expands this to -a + b. Due to operator precedence, the unary minus - binds more tightly than the binary addition +. This means a is negated first, and then b is added, which is likely not the intended behavior of negating the sum (a + b).

#include <stdio.h>

#define NEGATE_BAD(x) -x

int main() {

int a = 5;

int b = 3;

// Expected: -(5 + 3) = -8

// Actual: -5 + 3 = -2

printf("NEGATE_BAD(a + b) = %d\n", NEGATE_BAD(a + b));

return 0;

}

Demonstration of incorrect operator precedence with NEGATE_BAD(x).

Why (-x) is Preferred: Ensuring Correct Evaluation

The solution to the operator precedence problem is to always parenthesize macro arguments within the macro definition. When dealing with unary minus, this means using (-x) instead of -(x). Let's break down why:

-(x): Here,xis substituted directly. Ifxisa + b, it becomes-(a + b). The unary minus operator-then applies to the entire(a + b)expression, which is correct. However, this form is less common and can sometimes be confused with(-x).(-x): This is the more idiomatic and robust approach. The parentheses around-xensure that the unary minus operation is performed on the entire substituted argumentxbefore any other operators outside the macro can interfere. Ifxisa + b, it expands to(-(a + b)). The inner parentheses(a + b)ensure the addition happens first, and then the outer parentheses()ensure the negation applies to the result ofa + bas a single unit. This effectively isolates the argument and its negation from external operator precedence issues.

#include <stdio.h>

#define NEGATE_GOOD(x) (-x)

int main() {

int a = 5;

int b = 3;

// Expected: -(5 + 3) = -8

// Actual: (-(5 + 3)) = -8

printf("NEGATE_GOOD(a + b) = %d\n", NEGATE_GOOD(a + b));

// Example with multiplication

// Expected: -(5 * 3) = -15

// Actual: (-(5 * 3)) = -15

printf("NEGATE_GOOD(a * b) = %d\n", NEGATE_GOOD(a * b));

return 0;

}

Correct usage of (-x) in a macro to ensure proper evaluation.

Visualizing Macro Expansion and Precedence

To further clarify the difference, let's visualize the preprocessor's expansion and how operator precedence applies in each case.

flowchart TD

subgraph "Macro Definition: #define NEGATE_BAD(x) -x"

A[Input: NEGATE_BAD(a + b)] --> B{Preprocessor Substitution}

B --> C[Result: -a + b]

C --> D{Operator Precedence}

D --> E["Unary '-' on 'a' (highest precedence)"]

E --> F["Binary '+' with 'b'"]

F --> G["Final Evaluation: (-a) + b"]

end

subgraph "Macro Definition: #define NEGATE_GOOD(x) (-x)"

H[Input: NEGATE_GOOD(a + b)] --> I{Preprocessor Substitution}

I --> J[Result: (-(a + b))]

J --> K{Operator Precedence}

K --> L["Inner Parentheses: 'a + b' (highest precedence)"]

L --> M["Unary '-' on result of (a + b)"]

M --> N["Final Evaluation: -(a + b)"]

endComparison of macro expansion and operator precedence for -(x) vs (-x).

Side Effects and Macro Arguments

While parenthesizing arguments solves precedence issues, another common macro pitfall is side effects. If an argument with side effects (e.g., x++, func()) is used multiple times within a macro, the side effect will occur multiple times, leading to unexpected behavior. This particular issue is not directly related to -(x) vs (-x) but is a general macro caution.

For example, if you had #define SQUARE(x) (x * x) and called SQUARE(i++), it would expand to (i++ * i++), incrementing i twice. The solution for side effects often involves using inline functions in C99/C++ or GCC extensions like typeof and ({ ... }) blocks, rather than relying solely on macro argument parenthesization.

inline functions instead of macros.In summary, when defining C macros that involve unary operations like negation, always enclose the argument within parentheses, and then apply the unary operator. The form (-x) is the most robust way to ensure that the negation applies to the entire argument expression as intended, safeguarding against operator precedence problems. While macros offer flexibility, understanding their text-substitution nature and potential pitfalls is crucial for writing reliable C code.