How do negative margins in CSS work and why is (margin-top:-5 != margin-bottom:5)?

Categories:

Understanding Negative Margins in CSS: Beyond the Basics

Explore the mechanics of negative margins in CSS, their impact on layout, and why margin-top:-5px behaves differently from margin-bottom:5px.

Negative margins in CSS are a powerful yet often misunderstood tool for layout manipulation. While positive margins push elements away from their neighbors, negative margins pull elements closer, or even overlap them. This article delves into how negative margins work, their practical applications, and clarifies common misconceptions, particularly the difference between negative top/left margins and negative bottom/right margins.

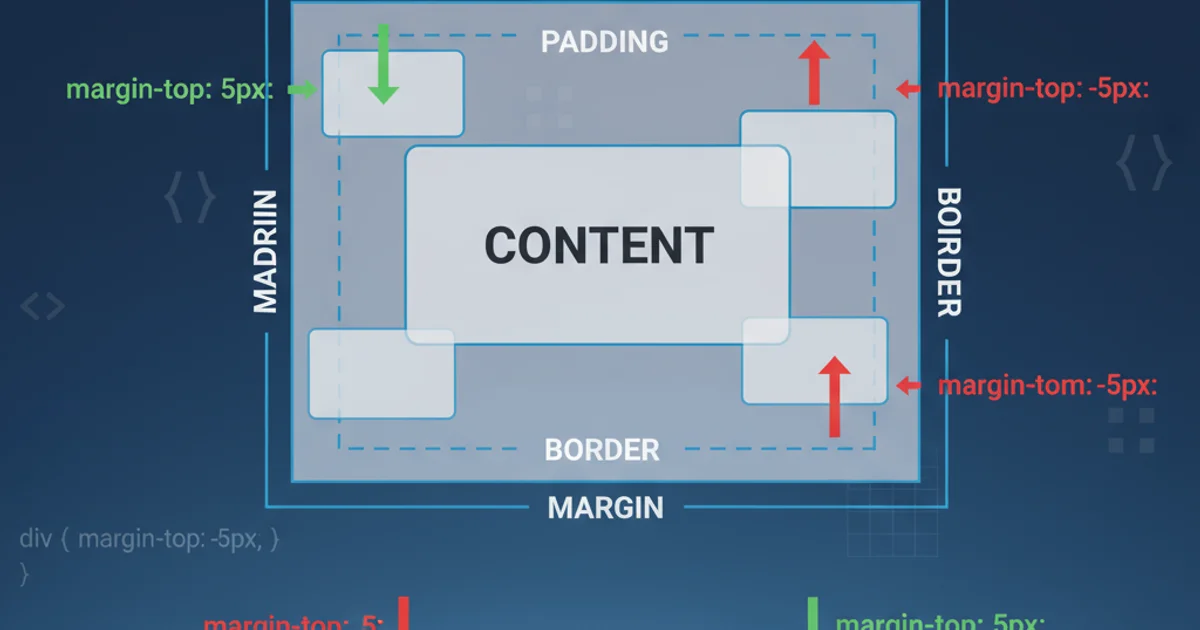

The CSS Box Model and Margin Basics

Before diving into negative margins, it's crucial to have a solid understanding of the CSS Box Model. Every HTML element is rendered as a rectangular box, comprising content, padding, border, and margin. Margins create space around an element, separating it from other elements. By default, margins are positive, pushing elements outwards. When a margin is set to a negative value, it effectively reduces the space between elements, or even causes them to overlap.

flowchart TD

A[Element Box] --> B[Content Area]

B --> C[Padding]

C --> D[Border]

D --> E[Margin]

E -- Positive Margin --> F[Pushes away]

E -- Negative Margin --> G[Pulls closer/Overlaps]

F & G --> H[Layout Impact]The CSS Box Model and Margin's Influence on Layout

How Negative Margins Work: A Detailed Look

Negative margins behave differently depending on the direction (top, right, bottom, left) and the element's display property. Generally, negative margins reduce the space allocated to an element's margin box. If the negative margin is larger than the available space, it can cause elements to overlap. This behavior is consistent across block-level and inline-block elements, though the visual outcome might differ due to how these elements occupy space.

.element-with-negative-margin {

width: 100px;

height: 100px;

background-color: lightblue;

margin-left: -20px; /* Pulls element 20px to the left */

margin-top: -10px; /* Pulls element 10px upwards */

}

Example of an element with negative left and top margins

The Asymmetry: margin-top:-5px vs. margin-bottom:5px

This is where the common confusion arises. While margin-top:-5px and margin-left:-5px directly affect the element's own position by pulling it upwards or leftwards, margin-bottom:-5px and margin-right:-5px primarily affect the subsequent elements.

margin-top:-5px: The element itself moves 5 pixels upwards, potentially overlapping the element above it. It reduces the space before the element.margin-left:-5px: The element itself moves 5 pixels to the left, potentially overlapping the element to its left. It reduces the space before the element.margin-bottom:-5px: This reduces the space after the element. It doesn't move the current element downwards; instead, it pulls the next element 5 pixels upwards, closer to the current element. The current element's position remains unchanged relative to its parent or preceding siblings.margin-right:-5px: Similar tomargin-bottom, this reduces the space after the element. It pulls the next inline element 5 pixels to the left, closer to the current element. The current element's position remains unchanged relative to its parent or preceding siblings.

This distinction is crucial for predicting layout behavior. Top and left negative margins affect the element's own starting position, while bottom and right negative margins affect the starting position of subsequent elements.

graph TD

A[Element A]

B[Element B]

C[Element C]

subgraph "Scenario 1: margin-top: -20px on B"

A -- "Normal Space" --> B_top_neg[B (moved up)]

B_top_neg -- "Normal Space" --> C_after_B_top_neg[C]

end

subgraph "Scenario 2: margin-bottom: -20px on A"

A_bottom_neg[A] -- "Reduced Space" --> B_after_A_bottom_neg[B (moved up)]

B_after_A_bottom_neg -- "Normal Space" --> C_after_B_bottom_neg[C]

end

style A fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style B fill:#bbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style C fill:#fbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style B_top_neg fill:#bbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style C_after_B_top_neg fill:#fbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style A_bottom_neg fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style B_after_A_bottom_neg fill:#bbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style C_after_B_bottom_neg fill:#fbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2pxVisualizing the impact of negative margin-top vs. margin-bottom

Practical Applications of Negative Margins

Despite their complexity, negative margins offer elegant solutions for various layout challenges:

- Overlapping Elements: Create visually appealing overlaps for images, text boxes, or cards.

- Breaking Out of Containers: Allow an element to extend beyond its parent container's width, often used in full-width sections within a constrained layout.

- Grid Adjustments: Fine-tune spacing in grid systems (like CSS Grid or Flexbox) where default gaps might be too large or need specific adjustments.

- Creating Negative Space: Achieve specific visual effects by reducing the perceived space between elements, making layouts feel more compact or dynamic.

- Centering with Unknown Width: In some legacy scenarios, negative margins combined with

left: 50%were used to center elements before Flexbox and Grid became widespread.

/* Example: Breaking out of a container */

.container {

width: 80%;

margin: 0 auto;

overflow: hidden; /* Important to prevent horizontal scroll */

}

.full-width-section {

width: calc(100% + 40px); /* Container width + 2 * margin-left/right */

margin-left: -20px;

margin-right: -20px; /* Or just margin-inline: -20px; */

background-color: #eee;

padding: 20px;

}

Using negative margins to break an element out of its parent container