What is the difference between 'git pull' and 'git fetch'?

Categories:

Git Pull vs. Git Fetch: Understanding the Core Differences

Demystify the fundamental operations of 'git pull' and 'git fetch' to effectively manage your Git repositories and collaborate seamlessly.

In the world of Git, 'git pull' and 'git fetch' are two of the most frequently used commands for interacting with remote repositories. While both are essential for keeping your local repository up-to-date, they perform distinct actions that are crucial to understand for efficient version control. Misunderstanding their differences can lead to unexpected merge conflicts, lost work, or an inefficient workflow. This article will break down each command, illustrate their processes, and provide best practices for when to use which.

What is 'git fetch'?

'git fetch' is the command responsible for downloading new data from a remote repository without integrating it into your local working files. Think of it as a 'read-only' operation that brings your local Git repository's knowledge of the remote up-to-date. It retrieves all the branches and their commits from the remote that are not yet present in your local repository. However, it does not modify your local working directory, your local branches, or your HEAD pointer. It simply updates your 'remote-tracking branches' (e.g., origin/main, origin/develop).

flowchart TD

A[Local Repository] --> B{git fetch}

B --> C[Remote Repository]

C --> D[Local Repository (updates remote-tracking branches)]

D -- No change --> E[Local Working Directory]

D -- No change --> F[Local Branch (e.g., main)]

style A fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style C fill:#ccf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style D fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2pxThe 'git fetch' process: retrieving remote changes without integration.

git fetch origin

# This fetches all branches from the 'origin' remote

git fetch origin main

# This fetches only the 'main' branch from 'origin'

Basic usage of 'git fetch'

git fetch to see what others have been working on without disturbing your current work. It's a great way to preview changes before deciding to merge them.What is 'git pull'?

'git pull' is essentially a combination of two other Git commands: git fetch followed by git merge. When you execute git pull, Git first fetches the latest changes from the specified remote branch and then immediately attempts to merge those changes into your current local branch. This means 'git pull' does modify your local working directory and your local branch history. If there are conflicts between the remote changes and your local changes, you will be prompted to resolve them.

flowchart TD

A[Local Repository] --> B{git pull}

B --> C[Remote Repository]

C --> D[Local Repository (updates remote-tracking branches)]

D --> E{git merge}

E --> F[Local Working Directory (updated)]

E --> G[Local Branch (e.g., main) (updated)]

style A fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style C fill:#ccf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style F fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2px

style G fill:#f9f,stroke:#333,stroke-width:2pxThe 'git pull' process: fetch followed by merge.

git pull origin main

# This fetches changes from 'origin/main' and merges them into your current local branch.

git pull

# If your current branch is tracking a remote branch, this will pull from that tracked branch.

Basic usage of 'git pull'

git pull if you have uncommitted local changes, as it can lead to merge conflicts that might be difficult to resolve, especially if you're new to Git.Key Differences and When to Use Each

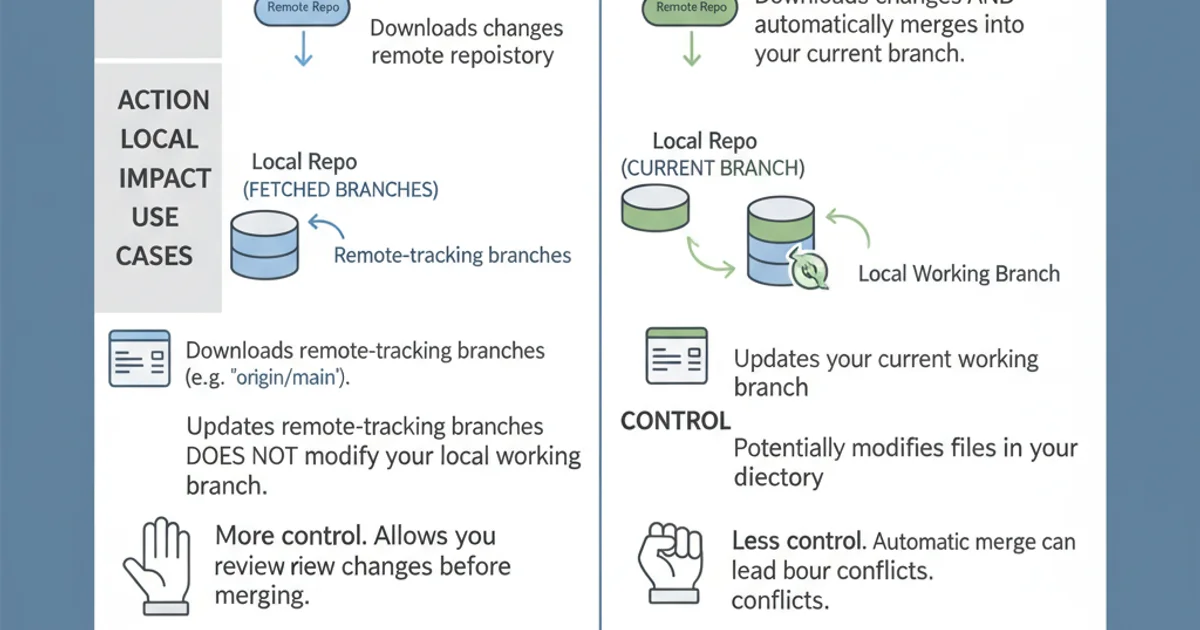

The core distinction lies in their impact on your local working directory and branch history. git fetch is non-destructive and gives you control over when and how changes are integrated. git pull is more aggressive, immediately integrating changes. Understanding this difference is key to a smooth Git workflow.

Comparison of 'git fetch' and 'git pull'

When to use git fetch:

- To see what's new: You want to check for updates on the remote without applying them to your local working copy. This allows you to review changes before merging.

- To avoid disrupting work: You're in the middle of a task and don't want to risk merge conflicts or changes to your current branch.

- To update remote-tracking branches: You simply want your local repository to have the latest metadata about the remote state.

When to use git pull:

- To update your local branch: You are ready to incorporate the latest changes from the remote into your current local branch and continue working.

- When your local branch is clean: You have no uncommitted changes, or you've committed your changes and are ready to merge the remote updates.

- For simple, linear updates: When you expect no conflicts or are confident in resolving them quickly.

Best Practices

A common and recommended workflow involves using git fetch first, then inspecting the changes, and finally merging them manually or rebasing. This gives you more control and reduces the chances of unexpected issues.

1. Fetch remote changes

Run git fetch origin to download all new commits and update your remote-tracking branches (e.g., origin/main). Your local working directory remains untouched.

2. Inspect changes

Use git log origin/main..main (or git log HEAD..origin/main) to see what commits are on the remote but not yet in your local main branch. You can also use git diff origin/main to see the actual code changes.

3. Integrate changes (Merge or Rebase)

Once you've reviewed the changes and are ready to integrate them, you have two main options:

* Merge: git merge origin/main (creates a merge commit)

* Rebase: git rebase origin/main (rewrites history, applying your local commits on top of the remote ones, often preferred for cleaner history)

git pull --rebase instead of a plain git pull. This automatically rebases your local commits on top of the fetched remote commits, avoiding extra merge commits.