What are carriage return, linefeed, and form feed?

Categories:

Understanding Carriage Return, Line Feed, and Form Feed

Explore the historical context and modern usage of control characters like carriage return (CR), line feed (LF), and form feed (FF) in text processing and programming.

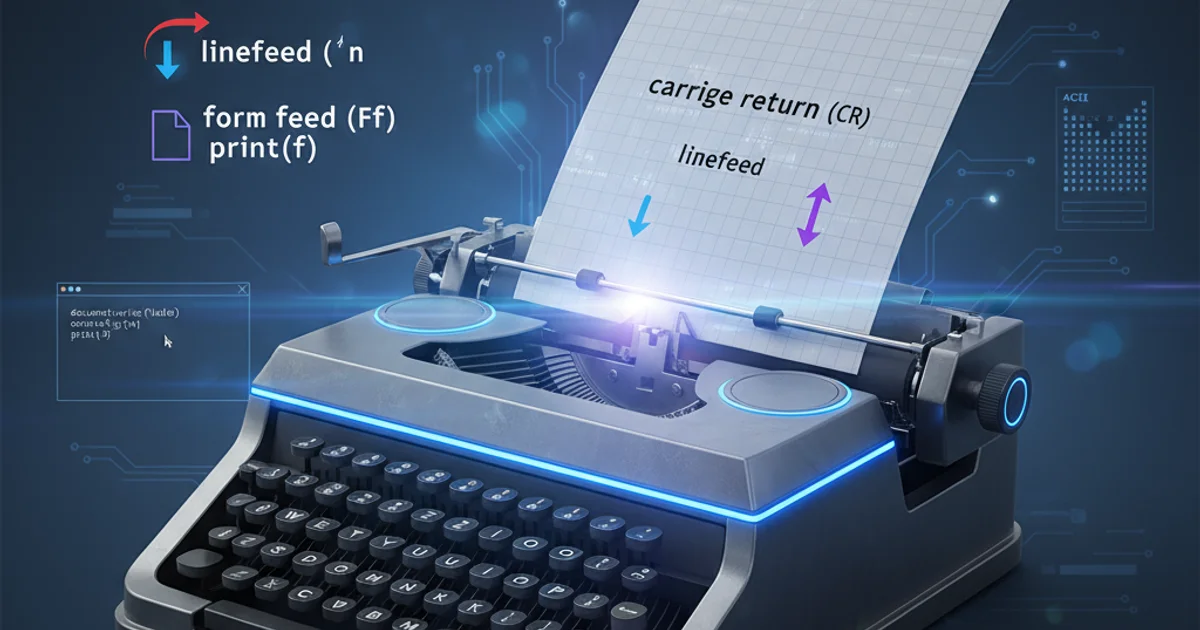

In the early days of computing and printing, special control characters were essential for formatting text and controlling output devices. Among the most fundamental are Carriage Return (CR), Line Feed (LF), and Form Feed (FF). While their original mechanical purposes have largely been abstracted away by modern operating systems and software, understanding their historical significance and current implications is crucial for anyone working with text files, cross-platform development, or low-level communication protocols.

Carriage Return (CR) and Line Feed (LF)

The terms 'Carriage Return' and 'Line Feed' originate from the mechanics of typewriters and early printers. A typewriter's carriage holds the paper and moves horizontally as you type. When you reach the end of a line, two actions are typically needed:

- Carriage Return (CR): Moves the print head (or carriage) back to the beginning of the current line without advancing the paper. On a typewriter, this would mean the next character would overwrite the first character of the current line.

- Line Feed (LF): Advances the paper by one line without moving the print head horizontally. On a typewriter, this would move the paper up, but the print head would remain at the same horizontal position.

In computing, these actions were translated into control characters:

- CR is represented by ASCII character 13 (0x0D).

- LF is represented by ASCII character 10 (0x0A).

Different operating systems adopted different conventions for representing a 'newline' or 'end-of-line' sequence:

- Windows/DOS: Uses a combination of CR and LF (

CRLF,\r\n). This mimics the traditional typewriter action of returning to the start of the line and then advancing to the next line. - Unix/Linux/macOS (modern): Uses only LF (

LF,\n). The assumption is that moving to the next line implicitly means starting at the beginning of that line. - Classic Mac OS (pre-OS X): Used only CR (

CR,\r).

This difference is a common source of issues when transferring text files between operating systems, leading to files appearing as a single long line or having extra blank lines.

flowchart TD

A[Typewriter Action] --> B{End of Line?}

B -- Yes --> C[Carriage Return (CR)]

C --> D[Line Feed (LF)]

D --> E[New Line Start]

B -- No --> A

subgraph OS Newline Conventions

F[Windows/DOS] --> G["CRLF (\r\n)"]

H[Unix/Linux/macOS] --> I["LF (\n)"]

J[Classic Mac OS] --> K["CR (\r)"]

end

E --> FEvolution of Newline Conventions from Typewriter Actions

import os

# Example strings with different newline characters

windows_text = "Hello\r\nWorld"

unix_text = "Hello\nWorld"

mac_text = "Hello\rWorld"

print(f"Windows text (CRLF): {windows_text!r}")

print(f"Unix text (LF): {unix_text!r}")

print(f"Classic Mac text (CR): {mac_text!r}")

# How Python's os.linesep handles it

print(f"\nOS's default line separator: {os.linesep!r}")

# Reading a file with universal newlines (default in text mode)

# This handles different newline types automatically

with open('example.txt', 'w', newline='') as f:

f.write("Line 1\r\nLine 2\nLine 3\r")

with open('example.txt', 'r') as f:

content = f.read()

print(f"\nContent read with universal newlines:\n{content!r}")

# Reading a file in binary mode to see raw bytes

with open('example.txt', 'rb') as f:

raw_content = f.read()

print(f"\nContent read in binary mode:\n{raw_content!r}")

Python example demonstrating different newline characters and os.linesep

Form Feed (FF)

The Form Feed (FF) character, represented by ASCII character 12 (0x0C), also has its roots in printer control. Its primary purpose was to advance the paper to the top of the next page. On a dot-matrix or line printer, receiving a Form Feed character would cause the printer to eject the current page and start printing on a new one.

While less common in modern text processing than CR and LF, FF still sees some specialized use:

- Source Code Delimiters: In some programming environments, particularly older ones, a Form Feed character might be used to visually separate logical sections of code within a single source file. Some IDEs or text editors might render this as a page break or a horizontal line.

- Printer Control: In niche applications dealing directly with legacy printers or specific print formats, FF can still be used to explicitly control page breaks.

- Documentation Tools: Some documentation generators or markup languages might interpret FF as a page break instruction.

For example, in C/C++, \f is the escape sequence for a form feed. When printed to a console, it often behaves like a newline, but its true purpose is page ejection.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("This is the first section.\n");

printf("This is still the first section.\f"); // Form Feed

printf("This is the second section, potentially on a new page.\n");

printf("End of document.\n");

return 0;

}

C example demonstrating the Form Feed character (\f)

core.autocrlf setting).Modern Implications and Best Practices

While the mechanical devices that inspired CR, LF, and FF are largely obsolete, the characters themselves persist in various forms. Understanding them is vital for:

- Cross-platform compatibility: Ensuring scripts, configuration files, and data files behave consistently across Windows, Linux, and macOS.

- Network protocols: Some protocols might specify particular newline sequences.

- File parsing: Correctly interpreting data from various sources.

- Terminal emulation: Understanding how terminal programs interpret these control characters.

Most programming languages provide convenient ways to handle newlines, often abstracting away the underlying CRLF or LF differences when reading/writing text files in 'text mode'. However, when dealing with binary files or low-level I/O, you might encounter these characters directly.

Best Practices:

- Use universal newline handling: When reading text files, most languages (Python, Java, etc.) offer modes that automatically convert various newline sequences to a single internal representation (

\n). - Be explicit when writing: If targeting a specific OS, use its native newline sequence. Otherwise, stick to

\n(LF) as it's the most common and portable for internal processing and Unix-like systems. - Configure version control: Set up Git's

core.autocrlfor.gitattributesto manage newline conversions automatically, preventing accidental commits of mixed newline styles. - Avoid hardcoding

\r: Unless you have a very specific reason (e.g., overwriting a line in a terminal), generally prefer\nfor newlines.